November 15, 2023

It is growing late. The wheel of time stops for no man, Andreas. I fear you must leave us.

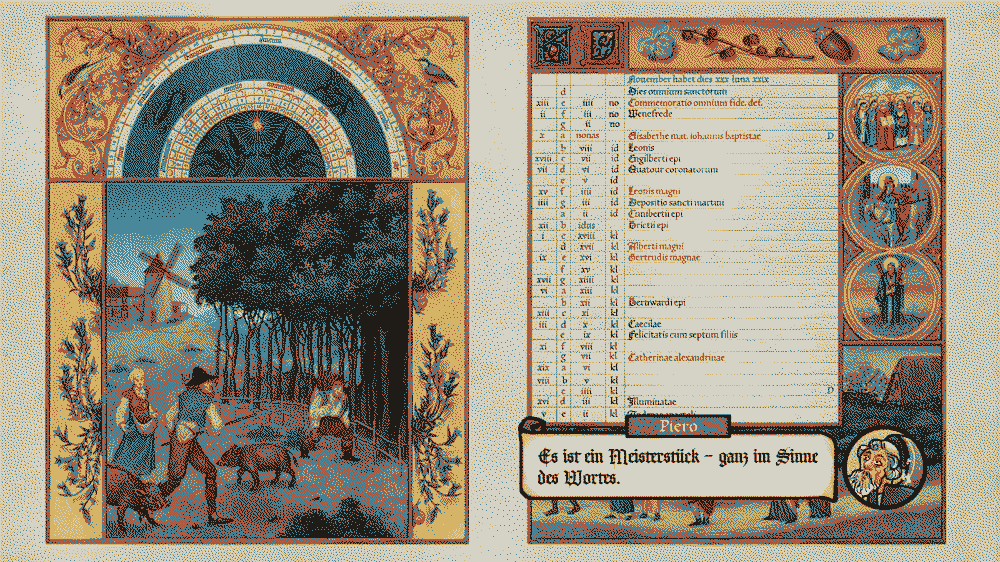

Precisely a year before the publication of this text, the historical narrative game Pentiment was released on November 15, 2022. During the quarter century that encompasses the game, November appears twice: once as the masterpiece that artist Andreas must complete before returning home, and again as the month in which printer Magdalene works on a new mural for the town of Tassing. Andreas dedicates his limited free time to the masterpiece, pressured by family who await its completion; while Magdalene must hasten to finish the mural before her dying father will succumb to his wounds. Pentiment and its cast are acutely aware of time and its material consequence.

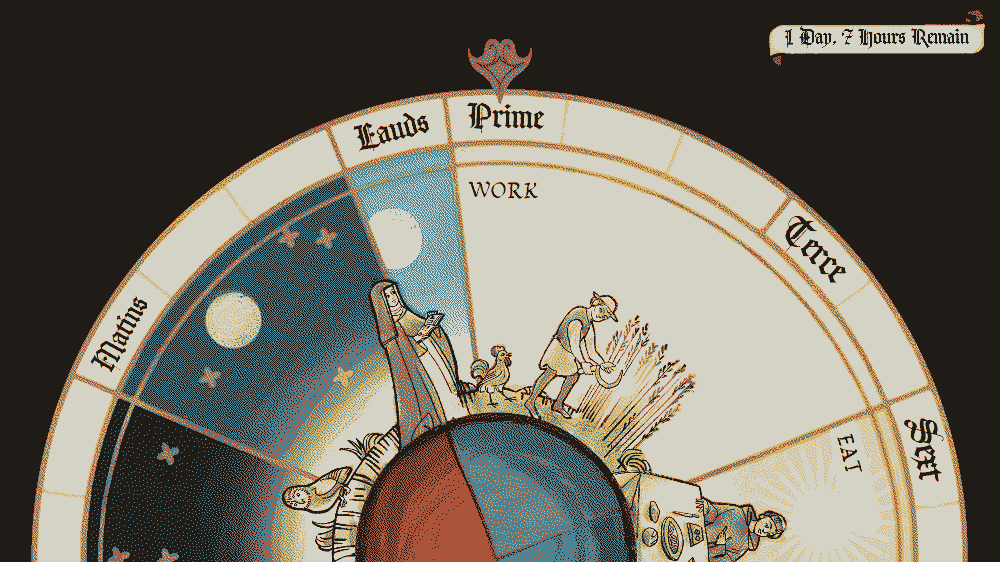

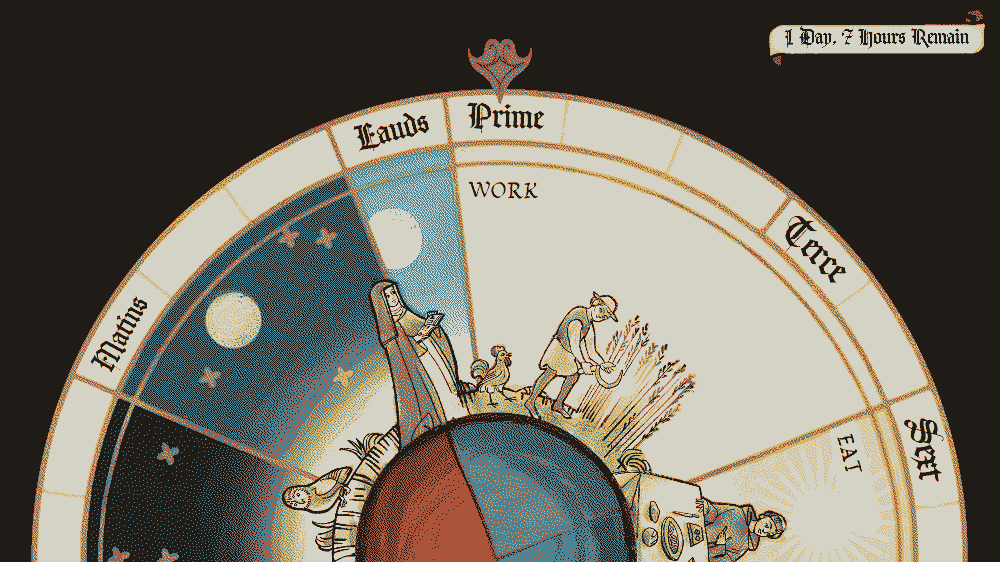

Acts I and II of the game are dictated by the Christian canonical hours which divide the day into specific times of work, rest, and prayer. Andreas is able to take a casual approach to these hours, as he receives only mild reprimands for arriving late to work. After the murder of a visiting nobleman, however, the clock suddenly feels less like a simple marker of time and more akin to a slowly tightening noose—for, of course, the killing of a nobleman cannot go unpunished.

Andreas takes it upon himself to find the true murderer when his mentor and dear friend is hastily accused of the crime. Due to the high status of the man killed, the judge will be arriving in Tassing within a few days; Andreas has a limited amount of time to explore his leads. It is through this investigation that the player, too, will soon feel the pressure of the ticking clock, for examining a single clue can expend half a day. Panicking and looking helplessly on as the hours fly by is the intended Pentiment experience. In a game without currency, inventories, or health meters, time is what the player must learn to manage—or attempt to manage, as they realize much too late that they cannot pursue every lead. The judge, with his executioner in tow, will arrive in town before the investigation can conclude.

Not having the whole picture is by design. The player isn't even afforded the comfort of manual saves, preventing an easy redo of events if they doubt their past actions. Andreas is questioned by the judge and gets a suspect killed; there is no turning back. Time marches on.

The investigation of Act II only raises the stakes. Seven years after the first murder, the town carpenter is found dead. All ire is directed toward the abbot, who has been steadily imposing restrictions and higher taxes on the townspeople. To prevent the destruction of the abbey, Andreas has, once again, voluntarily embroiled himself in a murder mystery—and, this time around, he must find a credible suspect before military force arrives to crush the burgeoning peasant's revolt.

Pressure mounts as townspeople wait to enact vengeance. Once the duke's soldiers appear on the outskirts of Tassing, Andreas must cut his investigation short and point the town toward a single suspect. Mob justice plays its role: the accused is set ablaze, and, as years of grief and fury rise to their boiling point, so too is the abbey library.

As ancient manuscripts burn and the duke's forces extinguish dissent, there is no save point to return to. Even when Andreas breaks loose from the player's grasp and hurtles toward his death, no one is offered the reprieve of a game over. The wheel of time continues ever on.

It is no wonder why the abbey, so often referred to as a "place out of time", must burn.

Death was no stranger to the people of the 16th century. Child mortality rates were high, and the Black Plague would continue to haunt Europe in recurring outbreaks. Great leaps forward in time bring the inevitable passing of familiar faces: though Acts I and II of Pentiment are bookended by the dramatic loss of life, it is between acts that death feels most close and mundane.

Genres of art that depict the universality of death were highly popular in the early modern era, including the vanitas and danse macabre—which was, fittingly, painted on the walls of the chapter house where the nobleman of Act I was killed. The most widely known of these genres, the memento mori, portrays not only death's inevitability, but also serves as a reminder of life's temporal nature. Such paintings frequently featured hourglasses or extinguished candles alongside a human skull. Skull-shaped clocks and watches were also in vogue, one such object inscribed with the Latin phrases incerta hora (the hour [of death] is uncertain) and vita fugitur (life is fleeting). It is apt, then, that time in Pentiment only becomes a finite resource when someone's life is on the line.

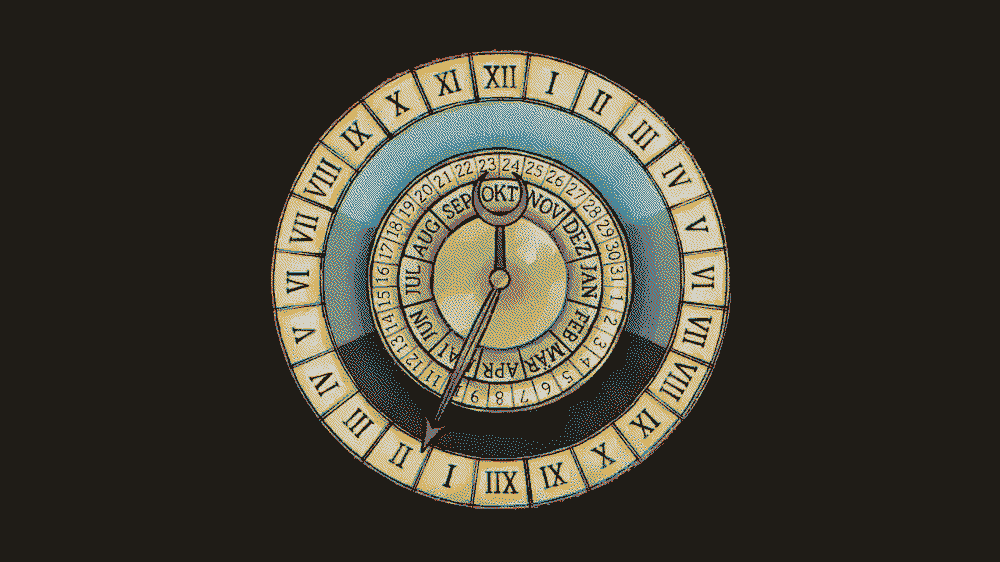

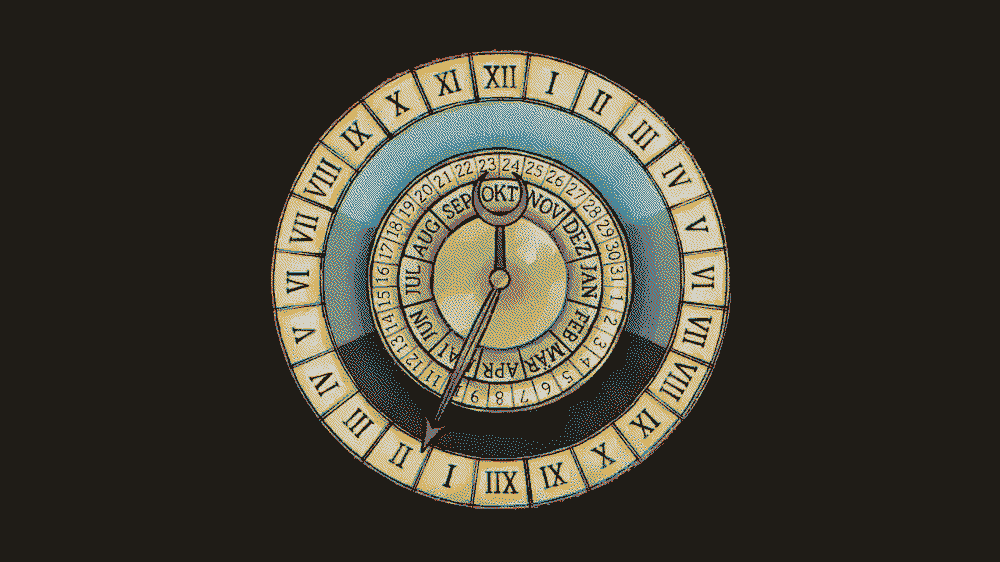

Eighteen years pass after the burning of the abbey. The monks have vacated and dispersed; Tassing has traded its abbot for a lord. The transition to a more secular rule is made most apparent by a new 24-hour clock, complete with dates and months. Gone are the holy and imprecise canonical hours as if they, too, had turned to ash all those many years ago.

Act III follows Magdalene, fervent artist and printer, who steps in to complete Tassing's historical mural after her father barely manages to survive a head injury. The damage is severe and Magdalene knows her father has, at most, a few months left. She begins work on the mural at once, driven by the belief that her father must see the final painting.

Despite the nebulous deadline that Magdalene imposes on herself, this new clock is more forgiving than the last: she can take her time and explore all the options available for what to depict in the mural. Magdalene's unhurried investigation is a welcome change of pace, lending a more quiet and contemplative quality to the final act. She, like Andreas, is able to explore the hidden areas of town that appear to be frozen in time—and, unlike Andreas, her natural curiosity is used for chronography rather than amateur criminal investigation.

The town of Tassing, as evidenced by Magdalene's research, seems to continually be in a state of temporal amalgam. A Roman aqueduct casts monumental shadows over the farms in which peasants unearth little amber sculptures from the Bronze Age; new constructions exhume ancient myth and concealed past; thousand-year-old tunnels form labyrinths deep below.

It is during the eve of Christmas that Magdalene determines the final subject of her mural, far beneath the foundations of Tassing where time has, seemingly, been put on pause. She learns not only the consequences of the player's previous decisions, but also uncovers local secrets that have lain dormant for centuries. And though yesterday's actions are immutable, how Magdalene chooses to narrate the past will forever shape her town's future.